Note from Jeremy: This post was co-written with Bethann Garramon Merkle (@CommNatural). She holds an MFA in nonfiction creative writing, has written over 300 articles and essays, edited a textbook, and works at the University of Wyoming as the Director of the Wyoming Science Communication Initiative. She edits the ‘Communicating Science’ section of The Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America.

********

A few weeks ago, we ran a poll about teaching science writing in university courses. We were, most specifically, curious about the reasons why people don’t teach writing in science courses. That poll generated great discussion, and 97 responses. While the poll itself is not a random sample of academic scientists, the results are still worth considering.

The majority or respondents teach writing in some or all of their courses:

Fig. 1

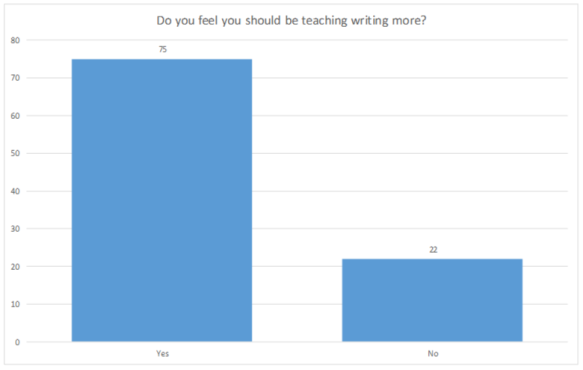

Even so, 77% (75/97) feel they should be teaching writing more than they do:

Fig. 2

However, the reasons we might anticipate – and the reasons we often hear – for not teaching writing, or not teaching it more often, did not dominate.* Interestingly, the same holds true in some other polls run on Dynamic Ecology. For example, there are a lot of widely discussed (and widely criticized) reasons for lecturing. And yet, when we ran a poll on why instructors lecture (or don’t), those stereotypical, maligned reasons proved to be rare.

Back to this poll.

Most respondents teach a diverse mix of courses. And, we don’t see much sign that class sizes* dictate how likely people are to teach writing.

Fig. 3

Surprisingly, people who report teaching only small classes (small undergrad and/or small grad) aren’t any more likely than others to say they teach writing in all their courses (4/25, 16%). Nor are people who teach only small classes any less likely than others to say they never teach writing (5/25, 25%, as compared to 21% among all respondents). Only 5/31 people (16%) who teach large undergrad courses (whether or not they teach anything else) report teaching writing in all courses they teach. That’s pretty close to the proportion of all respondents who report teaching writing in all courses they teach (20%).

Some 53% of respondents have no TAs (51/97; Fig. 4).** Unexpectedly, people who say that they teach writing in all their science courses actually are more likely to report having no TAs (13/19 report this) than are people who say they never teach writing (8/20 report no TAs). Which suggests TA support isn’t a major determinant of whether people teach writing or not. But the sample sizes are fairly small, so that could be a blip.

Fig. 4

Although the sample size is modest, we also don’t see any obvious sign that the graduate vs. undergrad course distinction affects people’s likelihood of teaching writing (Fig. 3). Furthermore, 11/15 (73%) people who only teach graduate courses (of whatever size(s)), and reported how often they teach writing, said they do so in some or all of the courses they teach (Fig. 3). That’s similar to the 81% of all respondents who teach writing in some or all of their courses (Fig. 3).

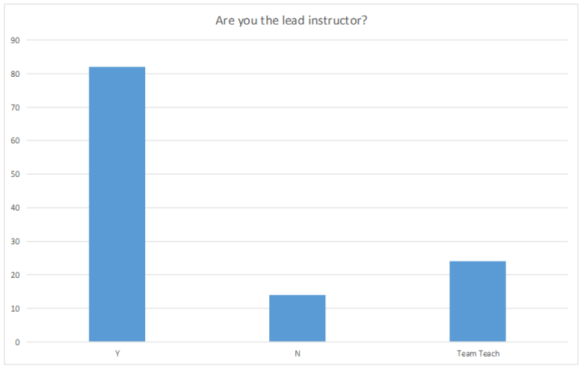

In 85% of responses (82/97), the respondent was the lead instructor:

Fig. 5

Since the predictable reasons – class size, class level (grad/undergrad), and access to TAs do not stand out as major reasons people do not teach writing, it’s worth a closer look at the rest.

No one reason for not teaching writing in science courses was dominant:

Fig. 6

Three of the top four reasons for not teaching writing related to lack of time for: grading writing-intensive assignments (70%; 42/60); supporting students (60%; 36/60); and planning (28%, 17/60). Lack of training in writing instruction came in third (30%; 18/60). None of the response options received zero responses, although only one person selected “I don’t care.”

There was no indication that people who prioritize course content, or simply don’t see writing instruction as their job, are getting that idea from supervisors and peers (Fig. 6).

Fundamentally, perceptions of time constraints dominate poll respondents’ reasons not to teach writing. These and lack of training are factors that can be effectively addressed through integration of best practices in writing pedagogy. The literature on professional skills needed by graduating students in ecology, wildlife biology (Atkins 2012; Maehr et al. 2002), and beyond (Druschkea et al 2018), also indicates writing and other core communication skills are fundamental to learning, doing, and sharing science (Yore et al 2004). Numerous studies and reports make clear that it is a detriment to exclude writing; rather it should be included in the disciplinary skills fully integrated into disciplinary work (Akkus et al 2007; Rivard 1994). While exclusion and/or isolation of writing skills remains a persistent issue, it can be overcome. If you are looking resources, check out Bethann’s most recent column in The Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America: “Writing Science: Transforming students’ science writing by tapping into writing instruction scholarship and best practices.”

Granted, it is considerably more challenging to address negative pressure from peers and supervisors. And, while our poll results indicate that pressure from peers and supervisors is a rare reason for not teaching writing, that doesn’t make it any less important to address. We’re curious, what have you done to address any of this, or any of the reported reasons for not teaching writing? And/or, what kind of support would you want or need to do so?

———————–

Notes

* In the interests of keeping our poll about teaching science writing in university courses short – and thereby hopefully getting more people to complete it – we skipped a few questions. In hindsight, perhaps we should have ask about career level or type of institution. Without that information (and in light of the non-representative nature of this and most polls), we are constrained in some of the inferences we can make.

** Of the respondents, 38% (37/97) did not indicate any reasons for not teaching writing. These same people all indicated that they taught writing in at least some of their courses.

Literature cited

Akkusa, R., M. Gunelb, and B. Handc. 2007. Comparing an Inquiry-based Approach known as the Science Writing Heuristic to Traditional Science Teaching Practices: Are there differences? International Journal of Science Education 29(14): 1745–1765.

Atkins, N. 2011. The Wildlife Society Blue Ribbon Panel Final Report: The Future of the Wildlife Profession and its Implications for Training the Next Generation of Wildlife Professionals. The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Druschkea, C. G., N. Reynolds., J. Morton-Aiken, I. E. Lofgren, N. E. Karraker, S. R. McWilliams. 2018. Better science through rhetoric: A new model and pilot program

for training graduate student science writers. Technical Communication Quarterly. 27(2): 175–190.

Maehr, D. S., B. C. Thompson, G. F. Mattfeld, K. Montei, J. B. Haufler, J. D. Kerns, and J. Ramakka. 2002. Directions in professionalism and certification in The Wildlife Society. Wildlife Society Bulletin 30:1245–1252.

Rivard, L. P. 1994. A Review of Writing to Learn in Science: Implications for Practice and Research. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 31(9): 969-983.

Yore, L. D., B. M. Hand, and M. K. Florence. 2004. Scientists’ Views of Science, Models of Writing, and Science Writing Practices. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 41(4): 338–369.

The crux, for me, is the topic sentence of your next-to-last paragraph. The poll data are clear, and represent a widely held opinion: teaching writing is time and labour-intensive. I think this opinion is correct. I was encouraged by that paragraph’s second sentence to entertain the possibility that I’m wrong (that teaching writing needn’t be time-intensive). But there was nothing there (and nothing I found in Bethann’s excellent essay linked to – please correct me if I’m wrong about this) to follow through on this counterintuitive argument! I teach scientific writing to upper-year and grad students. It’s very time-intensive and I simply couldn’t do what I do with those students with numbers large enough to reach our whole student body.

So this is the issue. We would like to teach much more writing. But teaching writing takes lots of time for feedback on repeated drafts, etc (and moving the focus from grammar to structure and clarity makes this more true, not less). Absent hiring a whole lot more faculty, I don’t know how to make this happen.

“So this is the issue. We would like to teach much more writing. But teaching writing takes lots of time for feedback on repeated drafts, etc (and moving the focus from grammar to structure and clarity makes this more true, not less). Absent hiring a whole lot more faculty, I don’t know how to make this happen.”

I agree with this. I too would like to hear some concrete ideas for teaching writing in science courses that can be implemented without taking massive amounts of time.

I know that we teach some writing in our big first year bio courses here at Calgary–the students have to write lab reports in first year, and I believe they do get feedback on drafts. But that’s possible because we have an army of TAs. And I don’t know the details of exactly what elements of writing are taught, or how they’re taught.

One thought I had was to change the sort of assignment we ask students to write. Lab reports and essays run several pages at least. What if we asked for shorter written assignments, say 1 page? That’s what my undergraduate intro philosophy course did. Each week, we had to write a page (sometimes two) summarizing some philosophy we’d read, or making a philosophical argument. We got feedback (on content, not grammar) and a mark each week. We didn’t get feedback on drafts, but that was ok because each assignment was similar to the others in many ways so the feedback on one assignment was in some ways transferable to the next. This approach obviously has many drawbacks as an approach to teaching *science* writing. It doesn’t teach students how to structure a scientific paper, or the conventions of scientific writing. And it’s still fairly time-consuming for the instructor so I’m unsure how big a class it would scale to (the answer would surely depend on how many other time commitments the instructor has). You could save further time by cutting back the number of assignments, though if you cut that back too far, at some point you’re no longer teaching writing.

Stephen and Jeremy, your thoughts on shorter and fewer assignments, with more drafts of each, are in line with the recommendations I’ve seen in the literature and heard from faculty in Rhetoric and Composition. More on that below.

But, first – while this won’t immediately help anyone actively teaching writing in science classes, I’d like to see more discussion at departmental (and higher) levels about how optional teaching writing in the sciences seems to be. Optional, of necessity (time, capacity, training, funding, etc.), granted; and yet, optional seems to be the default. On both a practical and philosophical level, making this aspect of skill development optional seems worth interrogating. Similarly, that writing instruction, and, indeed, the writing process, are time-intensive, are an excuse often used for justifying that instruction and training remain optional. However, it seems we’re feeding a negative cycle with this. Which, of course, cycles back to the overarching prioritization (or not) conversation. 🙂

Now, back to the shorter/fewer approach: The “Engaging Ideas” book by John C. Bean, which I focus on in detail in the piece in “The Bulletin,” does provide workable suggestions for how to make sure that the shorter and fewer approach still results in actual writing and training in it and disciplinary content…without being overly burdensome for the instructor. My hunch, though, is that a fundamental consideration is how much emphasis you want to put on teaching the structure of a science paper (scientific writing) vs being a clear/able (or ideally good) writer. I would argue (and I’m not proposing something new) that an ability to be a clear writer is a foundational skill for becoming a clear scientific writer. For example, in the undergraduate writing courses I’ve taught – some in the English Department, some in science departments – trying to follow conventions can be distracting or overwhelming if that is what is emphasized before having foundational capacity to organize thoughts, state them clearly, and use grammar and vocabulary effectively. To that end, we’re overhauling our junior/senior-level writing communicating in the discipline course this semester. We’re going to focus on a single overarching project, with a few components. The ultimate product will be a poster (a la science conference posters) rather than a long paper. And, we’ve split the class from a single 40+-student course into two sections of roughly half that number. We’re experimenting here, but the overarching goals are a) to reduce the student:instructor ratio (Stephen’s point) and b) build in more opportunities to revise shorter pieces of writing (Jeremy’s point). This latter one has been a successful approach for students I’ve worked with in a few previous classes, so we’re hoping that trend continues.

University of Washington requires additional credits in writing obtained through “W-course” credits. A “W-course” is a writing intensive course that’s designated separately, so you might have “Bio 220” and “Bio 220W”, where the later is the writing intensive version of the course. UW requires a minimum of 7 credits, but some departments may require more. Most of the local CCs have also created W-courses that satisfy the UW transfer requirements.

https://www.washington.edu/uaa/advising/degree-overview/general-education/additional-writing/

I like jeremys idea of smaller writing assignments, but you could take it down another notch or two.

You could simply have students copy verbatim small bits of good writing – definitions are great for this, because in science usually every word has a specific purpose and relationship to every other word. Having them copy helps them pattern those relationships. Then take, say, two dif defs of “species” and compare word for word – tear the writing apart.

Another possibility is to provide short answer (paragraph) study question(s) after each lecture or class, or maybe give 3 min at the end of class for one question?

I haven’t done it with a class but a possibly effective technique is to force people to read distill and compress. So give, say, 1-2 page reading ass and have students boil down to 8-12 line outline, where each line is a complete sentence. easier to grade too!

🙂

Yes! The distillation approach is another one often employed in rhetoric and composition courses, and it can certainly be leveraged in other disciplines.

For example, in a Communicating Across Topics in Energy course I taught a couple of years ago, we focused the entire 1st half of the semester on a single project. The end goal was a 1-minute audio piece which was based on a written script (not quite 200 words) developed from the preceding half-semester of students’ individual research, discussion, drafting and revision. Here’s a link to the syllabus for that one: https://commnatural.com/current-projects/. Scroll down to project 7 – Teaching Science Communication Courses, and select the syllabus link for Spring 2017, ERS 2500: Writing Across Topics in Energy; School of Energy Resources, University of Wyoming. Early drafts focused on ideas, intermediate drafts on organization and content, and later drafts on polishing. Peer review (with classmates) was built into the whole process.

In another instance, I helped design a curriculum for undergraduates that involved a synopsis project called an Expos(ition) Essay. Students were assigned an array of several research papers, and they chose one to summarize. They had a standardized template to fit their summary into, and the whole assignment was under 500 words. Both the template and the word length enabled students to revise numerous times and made instructor feedback more feasible.

Cool! I like distillation bcz it really forces people to ensure every word is well-used and conveys its intended meaning.

I really like the idea of student peer review – it gives students a greater diversity of views on their writing while off-loading the grading part.

Oh! Now I remember. When I worked in the mining industry, I was called on often to help other geos with rock descriptions in reports. It’s actually pretty challenging to write concise, readable descriptions of rocks, plants etc. So I think its a great writing assignment. For biology, say, you provide five plants, and give students, oh, say, 60 words per plant. You emphasize parallel structure so they’re really creating a template with the first description that they use for all the others. So if they work the first one out carefully, the rest are a breeze, which is a lesson all by itself

Back in the dark ages (1970s) when I was an undergraduate at Cornell, we were strongly encouraged to enroll in a ‘Scientific and Technical Writing and Editing’ course. It was one of the best courses I ever took. As I remember, there were few assignments. Two were one and three page essays on describing a piece of equipment and a building (and how they function). We sweated blood over those, and the skills/practices I learnt over those essays I still apply today. For the ‘big’ assessment, we chose a paper we had to write for any other course, so got two for the price of one. I’m sure there was more to the course but the lessons from those items have stuck with me for 40 years.

As the resident editor, I use a boiled-down version of Stephen Heard’s course at our research institute here in New Zealand for experienced staff and new post-docs. They think it’s great and I have noticed a difference in their reports and publications.

Your description projects sound really challenging!

I am late to the party here, but I agree wholeheartedly with the smaller assignments idea. A couple of examples that have worked well for me (and colleagues):

One way to go about it in introductory labs is to build towards a scientific paper by only writing small parts. Start with a results section or even a figure caption – describe data clearly. Then move on to methods+results, or results+discussion. Scaffolding up towards the full paper lets them focus on the authorial goals of each section.

Another approach I have used for intermediate courses is “News+Views” type assignments – short, accessible distillations of a specific scientific study. In my Ecology class (25-30 students, no TA), each student picks a paper from the recent literature (4th week), writes a “Views” piece for a scientific audience (~1000-1200 words), then a “News” piece (press release/blog post style) for a more general audience (~350-500 words). Each part has a draft, but it is not too onerous, and sometimes just drafting and revising (as a process) is more important than the particular feedback a student gets on a draft.

Finally, another idea is to have students include a brief cover letter with their final draft, explaining their changes and strategies – gets them to think about having goals as a writer and not just trying to check criteria off of a rubric.

Great post! Thanks, and I am sorry I missed the more active period of discussion.