Early in the semester during an Intro Bio class, a student asked about whether it’s ever possible for individuals of two different species to breed. That led to discussion of zebroids and, at some point in the back and forth, I mentioned that Homo sapiens had successfully interbred with Neanderthals. At least a quarter of the students (maybe even half) were visibly surprised—and I didn’t even explain that the evidence is this happened repeatedly! (Don’t worry, we covered that in a later lecture.) That night, I was making lunch for my kids and thinking about that moment in class, and I thought “Just wait until I tell them how much of their genome is viral!”

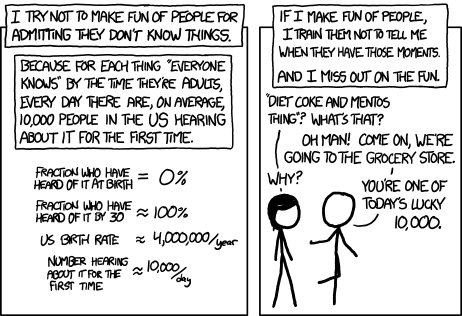

There are parts of teaching Intro Bio that are hard or annoying or both. But there are some parts that I absolutely love, and one of those is routinely getting to introduce students to things that are literally jaw-dropping. It makes me think of this xkcd:

It is always a highlight of my day (week!) when we have one of those moments in class.

So, in that spirit, I present an incomplete list of things that blow the minds of Intro Bio students (many thanks to my colleague Cindee Giffen for helping me with this list!):

- (Almost) all of your cells contain all of your genes

- Humans interbred with Neanderthals (repeatedly)

- About 8% of the human genome is viral in origin

- Plants get infected by viruses. (This comes up because I show a thermal image of a plant leaf that has been infected by a virus when talking about respiration. Speaking of which…)

- Plants respire

- There are photosynthetic organisms that are not plants

- Male anglerfish fuse to the female

- Damselfly penises

- Gerboas

- Taxonomy, including humans are fish, whales are mammals not the things we generally mean by “fish”, and birds are dinosaurs. Or, to quote a former student, “So, sharks are fish, dolphins are mammals, whales are mammals too, and penguins are birds, and birds are dinosaurs, so penguins are dinosaurs?!?”

- Fecal transplants

- Judas goats

I sometimes think that, if we filmed students while introducing those things, we would get really, really good reaction gifs.

The above list are mostly factoid sorts of things, but there are some bigger conceptual things that are definitely mind-bending for some students. Three that immediately spring to mind are:

- The same thing can be an ancestral or derived trait, depending on your frame of reference

- The way you can zoom in through taxonomy, sort of like you’re zooming through Google Earth (for example, humans are eukaryotes and animals and deuterostomes and vertebrates and mammals and primates and apes and hominins)

- Food webs — that something happening way over here in a food web can influence something way over there, and also the differences between how energy flows and matter cycles

Another thing that definitely blows their minds is that ecology involves math. I address this head on now at the start of the population ecology class, and my sense is that helps, but it still really surprises many of them when equations start appearing.

I initially started compiling this list because I thought it might be interesting to others. But I’ve found it has helped me during a very busy, challenging semester — it’s ended up being a really nice way of noting the little things that are fun that I might otherwise just blow right by in a frenzy of trying to get things done. (It’s also led to me adding notes to the front of my lecture notes that say things like “damselfly sex”, in an attempt to remember to add that to the list.)

So, I’m curious:

- What things have you found blow your students’ minds (in a good way!) And

- Do you have any routines or other things that help you note the little, fun things that occur while teaching?

Adactylidium mites. The closest thing to a Darwinian Demon I know of. Female has one son and several daughters inside her and her daughters all mate with her son. Daughters then chew their way out of her, already pregnant with their brother’s offspring. Mother dies, brother dies.

Out of context, that entire paragraph sounds like a horror-themed folk story.

Goldfish are more closely related to humans than they are to sharks

Epigenetics. Lamarck’s revenge as noted in P.Ward’s title (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018)

It blows my mind as well.

Not Intro Bio, but in my Entomology course I break in the middle of each lecture for “Bug of the Day”, which is often an insect or other arthropod that blows my own mind. For example: Sminthurides, the water springtail, whose mating behaviour involves a female carrying around a male by his antennae, and lowering him to the water surface like a little Pez dispenser every time she “wants” a spermatophore. I’ve been posting most of these in a very Twitter thread: https://twitter.com/StephenBHeard/status/1180080631868510210?s=20

Also, can concur on damselfly penises. Both of them.

Good topic. A few more that spring to mind from my Ecology and Evolution class:

1) That there are many more species of animals than there are of plants

2) The species richness of insects

3) Haplodiploidy, and that a male honeybee can’t have a son but can have a grandson

4) Parasitoidy

5) Hyperparasitoidy

6) Naked molerats

7) The range in testis size in bats, its relation to mating system, and its negative correlation with brain size

8) Southern elephant seals as extreme examples of sexual selection/dimorphism

In population ecology: chaotic population dynamics, as illustrated by the discrete time logistic equation.

Just asked our lab slack to see what our undergrads say, will report back.

When talking about distribution of plants and animals – The whole concept of our globe in terms of North on top and South on the bottom is arbitrary. Relative size of different places (Continent of Africa vs. US to most American College students blows them away). Showing them plate tectonic shifts and how different continents were attached.

This year, I gave my lecture on chaos from logistic growth on Halloween because SPOOKY! Definitely saw some brains explode in a good way. Showed them using https://jebyrnes.shinyapps.io/logistic_growth/

Unpopular opinion here: “humans are fish” — not by how the word “fish” is used by 99.999% of humans. And I would argue these 99.999% are not wrong. Humans are Osteichthyes or Osteichthyians yes but “fish” is a non-scientific term. Its definition is entirely determined by the norms of the group using the term, so it has different meanings depending on what group you are in and the definition will change over time and space. This can be a feature or a bug, but that is language. It is not “correct” in any way scientific sense to say “humans are fish”. It is political or rhetorical yes, but not scientific. More problematic usage might be informalizations of taxonomic names. Birds are dinosaurians but are they dinosaurs?

Sorry to start off with my curmudgeon voice. This is an excellent, motivating post. A smattering of others

0) a virus is not a living thing

1) a huge (92%?) of our DNA is non-coding or not obviously part of transcriptional regulation — https://sandwalk.blogspot.com/2008/02/theme-genomes-junk-dna.html

2) All cells have the same genes but we have abundant somatic mutations — https://sandwalk.blogspot.com/2017/04/somatic-cell-mutation-rate-in-humans.html

3) human chimeras — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lydia_Fairchild

4) spores launched at 180,000g — https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0003237

5) the little red-back salamanders in the woods out back “breathe” through their skin

6) an air-breathing organ (or “lungs”) is probably a primitive trait for ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygia) (or not breathing air is derived).

Yeah, lungless salamanders make a big impression. Lest one think it’s restricted to tiny sallies, Hellbenders have lungs but don’t really use them to breathe.

In a similar vein, fishes’ air bladders come from lungs, not the other way around (sorry Darwin!).

Not all animals, or even all vertebrates, require sex to reproduce.

That we are still ‘discovering’ primate species. And the strangeness of talking about ‘discovering’ species that people have lived with and known of for millennia.

In particular, the recently ‘discovered’ snub-nosed monkey that is easy to find in the rain because its upturned nose collects water and forces it to sneeze.

“The way you can zoom in through taxonomy, sort of like you’re zooming through Google Earth”

Not sure if you were aware of this website when you wrote that sentence: http://www.onezoom.org/

It allows you to zoom through the tree of life using fractal-geometry algorithms as those used in Google Earth…

I wasn’t! Thank you!

Oh yeah, 20% of the world’s oxygen production comes from diatoms. Although I have to confess I’ve never been able to track down the paper this ‘fact’ come from.

Hmm, yeah, I’ve heard that too, but I don’t think I’d share an amazing factoid in class if I couldn’t track down the source.

This could be a good quantitative assignment for an intro bio class. Here is my very quick back of the envelope calculation.

0) Assume O2 comes from diatoms and plants only

1) global biomass of diatoms is 500 tg C = 500 x 10^12 g C, or 0.5 x 10^15 g C (https://www.earth-syst-sci-data.net/4/149/2012/)

2) global biomass of plant is 450 Gt = 450 x 10^15 g C. Call this 500 Gt. (https://www.pnas.org/content/115/25/6506)

3) Assume all plants are trees. 99% of plant is dead cell so not generating O2, so biomass of plants generating O2 is .5 x 10^15 g C, which is same as diatom biomass (assumes that all non-wood cells are photosynthetic).

4) This would give us 50% O2 from diatom and 50% from plants. This ignores cyanobacteria, which are a big component so both diatom and plant contribution will drop. So add cynobacteria…

5) cyanobacteria biomass is 3 x 10^14 g C (https://bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu/bionumber.aspx?s=n&v=3&id=111370)

so diatom = .5/(.5 + .5 + .3) = 38%

good discussion would include what are assumptions and how sensitive the result is to these assumptions.

And, I have a miscalculation — the mass of living plant tissue is .01 * 500 x 10^15 g C = 5 x 10^15 g C (not .5 x 10^15 g C) so diatom = .5/(.5 + 5 + .3) = 9%. Now correct for photosynthetic fraction of living cells and that will get us closer to 20%

They are definitely shocked to learn that cyanobacteria oxygenated the atmosphere.

Re: anglerfish, I’ll just leave this here. 🙂

The last thing that blew my mind, and I can’t stop thinking about it is how old is the idea that a species can get extinct.

Even though now that sounds like one of those very obvious things, the paradigm shift from “beings are plentiful and a constant part of the great chain of being”, to “different life forms used to exist, and they don’t anymore” only started to occur around 1800’s with the work of Cuvier and others. It still blows my mind how late in the development of though did someone connect the dots…

That’s a good one. Related to this, it was not widely understood until surprisingly recently (not sure exactly when, but likely from a roughly similar time period) that fossils were the remains of once-living organisms. It sounds obvious now, but it’s not at all obvious how a clam shell made out of rock could get into the side of a mountain hundreds of miles from the sea. And in an era when most people never traveled more than a few miles from home, it would not be obvious what fossils of, e.g., starfish were if you had never seen living relatives.

That the atoms that make up our DNA were forged in stars billions of years ago, and that star exploded, spreading those atoms to out corner of the universe.

I briefly cover Alan Turing’s life when we cover Turing mechanisms/diffusive instability. A lot of my students are visibly shocked by just how tough it used to be to be a gay man. Which while less fun is its own kind of hopeful.

Every year for our Darwin Dinner here at Calgary, I give the attendees (who include some ecology undergrads) a little talk on Darwin’s life and times. It blows the undergrads’ minds to learn that Darwin had only recently finished his undergraduate degree (well, the Victorian equivalent of an undergraduate degree) when he left on the Beagle voyage.

Question Meghan: does it worry you at all that some of the items on your list are things Michigan intro bio students presumably should’ve learned in high school? #1 and #5 in particular, and perhaps #6 as well.

before worrying about the students, I’d be interested in having some idea of what fraction of high school biology teachers have a well-thought out understanding of these items, especially 1, 5, and 6.

I actually wouldn’t expect any of those items besides 1, 5, and maybe 6 to come up in high school, or to necessarily be familiar to all high school biology teachers. Should’ve been clearer about that. But I’d definitely expect 1 and 5 to be well-understood by any high school biology teacher, and probably 6 as well. (Well, I’d also expect any high school biology teacher to know a few famous bits of taxonomy. Such as that whales are mammals not fish, and that birds are derived from theropod dinosaurs.)

Now I’m wondering how you’d rank-order those 12 items in terms of how widely-known they are among anyone who’s not Meghan. I mean, there are a few items on that list even I wasn’t totally familiar with, and I’m a PhD-holding biologist! I’m of course generally aware of the many amazing penile adaptations that have evolved under sexual selection, but I didn’t know the specific example of damselfly penises. I knew that some non-negligible fraction of the human genome is of viral origin, but I didn’t know the exact fraction. And I knew the gerboas are small rodents that hop around, but I didn’t know that they’re capable of running and skipping too, and that they switch among all 3 gaits to help achieve unpredictable movement. So I feel like those are maybe the least well-known items on the list? The one about anglerfish males seems pretty obscure too, thought it’s one I happened to know. But “plants get viruses” would be intermediate, I’d guess, since gardening’s a pretty popular hobby and lots of gardeners will know it.

To be clear: I don’t think everything on the list is essential for students to know. But they can be useful examples at different points, and I like to try to introduce some natural history along the way, since there’s so much cool stuff out there to introduce them to!

I have no idea what high school biology teaches about plant respiration, but it is a major source of confusion for many of our students.

In my lab: protist “morphology”, and the plasticity thereof. It’s amazing what shapes you can make with a single cell. Two favorite examples: Lacrymaria olor (“tears of the swan”):

and the three morphs of Tetrahymena vorax. It has an inducible defense and an inducible *offense* (the video below doesn’t show the defensive morph, though the narrator mentions it in passing):

That these words – “An atmosphere of [CO2] would give our earth a high temperature…” – were written in 1856. And predictions about human CO2 emissions and temps began shortly thereafter.

Foote, E. (1856). ART. XXXI.–Circumstances affecting the Heat of the Sun’s Rays. American Journal of Science and Arts (1820-1879), 22(66), 382.

Human chimeras! This is a jaw-dropping statement: “In need of a kidney transplant, she was tested so that she might find a match. The results indicated that she was not the mother of two of her three biological children.” https://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/17/science/dna-double-take.html

!!!

I remember hearing about this when it came out! Definitely mind blowing!

Animals, even things like spiders, having uniques personalities (timid, bold, explorative, etc) always seems to blow some minds and leads to a lot of questions!

Also, the fact that invertebrates have nervous systems and react to painful stimuli also seems to surprise a lot of my students.

Re: gerboas, having watched the linked videos, now I want to learn more about how they manage to move so unpredictably. I wonder about this because it’s very hard for people to consciously behave unpredictably. For instance, if you ask a bunch of people each to just pick a number at random between 1 and 10, you won’t end up with a uniform distribution of picks. And if you ask people to write down a random sequence, say a random sequence of coin flip outcomes or a random sequence of digits, the sequence invariably will have a lot of non-random structure to it.

Good point! I have no idea if anyone has looked at that, but it would be an interesting topic!

It was very interesting serving on a search committee recently for an evolutionary/comparative biomechanics faculty position. Good research statements and good job talks are a fabulous way to learn where the cutting edge is. Anyway, the next big things (well, some of the next big things) in evolutionary/comparative biomechanics are evasive movement, and movement over rough terrain.

Evolutionary/comparative biomechanics is super cool. Like, everything about it is super-cool–the questions, the organisms, the techniques, the applications…I really like what I do, but if I was forced to go back in time and choose differently as an undergrad, knowing what I know now, instead of working with David Smith doing community ecology, I might work with Joan Edwards and do evolutionary/comparative biomechanics. Oh well, two roads diverged in a wood and all that.

In intro biostats: the Monty Hall problem when teaching basic probability theory

I try to convey that the Central Limit Theorem *should* blow their minds, but only a minority ever seem to be blown away by it

Yes! I actually show the “mind-blown” gif when I teach the CLT and I feel like it blows my mind every time…but they are unmoved.

Thanks, I’m glad to know it’s not just me that has this problem!

I teach stats, and I also find the students are not always as amazed as they might be. But at this point in the course, the normal distribution is the only distribution they know by name (we haven’t covered t, F, chi-square, etc. yet). So for them it’s not so shocking that the answer would turn out to be normal — that’s the only choice they’re aware of.

Where the mass in plants ultimately comes from. They seem to think of plants as sucking their essence out of the soil. But N, P, and S plants is so much smaller than C, H, and O! Undergrads seem to have a hard time wrapping their minds around the idea of the mass coming from the invisible atmosphere rather than the “solid” stuff they can see.

Also: meristematic growth. Can’t tell you how many times I have had to prove to a student that their houseplants are growing from the tips, not the base.

“Where the mass in plants ultimately comes from. They seem to think of plants as sucking their essence out of the soil. But N, P, and S plants is so much smaller than C, H, and O! Undergrads seem to have a hard time wrapping their minds around the idea of the mass coming from the invisible atmosphere rather than the “solid” stuff they can see.”

Huh, interesting. How do you disabuse them of that notion? Just show them data? Or point to something in their own everyday experiences? I mean, they’ve presumably all watched fires burn wood and leaves to ash. Can you build on that to get them to realize “Oh, right, that wouldn’t happen if plants were mostly made of N, P, S, K, etc.”?

Great post and thread. This one blows my students’ minds too. To teach it I treat it as a mystery: look at this acorn that turns into this giant tree, where did all this mass come from? Then we walk through van Helmont’s classic experiment and its implications (including his erroneous interpretation). It would be fun to actually *do* that experiment, but I haven’t found time in my lab schedule for this…

Yes! I can’t believe I forgot to include this on my list! This is totally mind-blowing for them. In some years, I’ve shown that old video of Harvard students at graduation who are totally stumped by this.

I second (third?) the “humans are fish” observation. My go-to is “fungi are more like people than plants are”. Also, birds are dinosaurs.

Even phylogeneticists use ‘gross similarity’ as a first order approximation of phylogeny, when we know they are very different things, so its fun to see where this assumption leads us horribly astray.

Yes, where fungi are on the tree of life relative to humans is also surprising!

Mice are more closely related to humans than they are to “marsupial mice”

Mitochondria are actually the result of an ancestral bacteria engulfing an archaea

Echidnas have a four-headed penis

Snakes and lizards have two penises (hemipenes)

Fungi are more closely related to humans than they are to plants

Birds are dinosaurs

Baby chicks can count

There are 20,000 species of bees in the world

Honeybees are not threatened with extinction

Monogamy and pair-bonding have been important in human evolution by allowing extended parental care of energetically-expensive offspring, and by reducing violence and allowing extreme cooperation between males and thus building civilisation

GMOs don’t give you cancer

Parasitic wasps that lay eggs in caterpillars.

Why you should close your toilet lid before you flush, especially if you keep your toothbrush in there.

What live nemotodes look like under a microscope.

Great post!

lots of weird sexual organs mentioned. two good ones for comparative vertebrate anatomy or a side story for human anatomy and physiology is

1) female spotted hyena’s pseudopenis – it’s not a clitoris (because it contains the vagina and urethra) and its not a penis (because it contains a vagina) and they give birth through it (because it contains a vagina. The beauty of this anatomy all comes together with a little knowledge of the development of the internal and external genitalia in mammals. This video could be fun: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Egtbs-go4Q

2) the female Didelphis virginia has two vagina’s, hence its name. The male has, wait for it…a bifid penis (so very much like Darwin’s moth and orchid). The beauty of the female anatomy all comes together with a little knowledge of the development of the internal and external genitalia in mammals. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jemt.22178

I love the Neanderthal-Sapiens story. Tim Flannery tells it so well in Europe: A Natural History.

I get a lot of confused looks when I talk about climate change being a relatively small threat to biodiversity compared to land use/fragmentation and invasive species. A lot of the students are in sustainability courses too, might be the reason?

Got a bit of a reaction when I talked about how recently species like rhinos and elephants went extinct in Europe too.

Pingback: Recommended reads #160 | Small Pond Science

Most children’s books talk about plants getting food from soil. Its actually a bit of a shock to realise they get a lot of their ‘food’ from the air.

I guess it’s blowing their minds in a slightly cruel way, but when I was a TA for Genetics I liked to do this when we got to the part of the course about human genetics and drawing family trees (squares for males, circles for females, filled for whatever interesting phenotype, often hemophilia):

“You see on this diagram the closed loops formed by relatives marrying and having children. We often talk about inbreeding in the royal families of Europe. This is how that looks when we draw it all out.”

*discussion of inbreeding, probabilities of inheriting identical-by-descent alleles, why most harmful mutations are recessive ensues*

“OK, we’re talking about cousins here. We’ll leave the details of what ‘third cousin twice removed’ actually means for later, but for now we’ll stick with first cousins.”

“Most people have at least one first cousin. And most of those people have at least one first cousin of the opposite sex to themselves.”

“I want you to picture your opposite-sex cousin in your mind. Have you got them? You can see them?”

*pause*

“Now they’re naked”

Never fails to get a few shocked looks.

The slow process of convincing students that common names of organisms are often useless or misleading: Sea lions didn’t evolve from lions. There are a bunch of very different things named “dolphin”, likewise “buzzard”.

The long, long list of species that people assume are native to their area but were introduced sometime after 1500 A.D. Horses in the Americas, potatoes, tomatoes, and corn (maize) in Africa/Asia/Europe.

Pingback: Dynamic Ecology year in review | Dynamic Ecology

Pingback: TWiV 584: Year of the coronavirus | This Week in Virology

Here are some of my personal favorites:

– There are approximately 37.2 trillion cells in the human body

– 8% of human DNA is made of viruses (endogenous retroviruses that is)

– Male jack jumper ants have 1 chromosome!