Over the past year+, my fellow Intro Bio instructors (Cindee Giffen, Jo Kurdziel, and Trisha Wittkopp) and I have invested a huge amount of effort in overhauling the course. The most substantive changes we made involved 1) moving some content outside of class, 2) frequent quizzing (on the readings they are supposed to do before class as well as harder questions about material covered in class), and 3) increasing the amount of active learning occurring in the classroom (through the use of clickers and in-class activities).

What was the effect of all this effort? We all had a sense that we were asking more of the students and like they were rising to the challenge. But a vague sense of that is not a particularly convincing argument to give colleagues, especially given the substantial stress that accompanied the first semester of teaching with this new model.

I realized that one way to compare things was to compare exams from Fall 2012 (traditional lecture format) and Fall 2014. (I was involved in writing exams both semesters, which is why I chose those semesters.) When I said above that we had a sense we were asking more of students, what I mean is that I felt like we were asking students to really process information and think deeply on exams, rather than to memorize a lot of facts and then regurgitate them.

Given that impression, we decided to apply Bloom’s taxonomy (another link) to exams for the two years. Bloom’s taxonomy allows you to assess where questions fall on a 1-6 scale from lower order thinking (simple recall of facts) to higher order thinking (analyzing and evaluating information that is presented). We decided that we had four of these levels on the exams:

- remembering – that is, basic recall

- understanding – for example, given a new example, being able to recognize a concept we’d covered in class

- applying – for example, recognizing what equation needed to be used, figuring out what information from a question is relevant to the equation, and correctly solving

- analyzing – giving students completely new data that they had to interpret in light of concepts covered in class, or having students make predictions (verbally or graphically) based on a novel scenario.

To give examples of a multiple-choice question in each category:

Level 4 (I wrote this question on an early morning run. Multitasking FTW!):

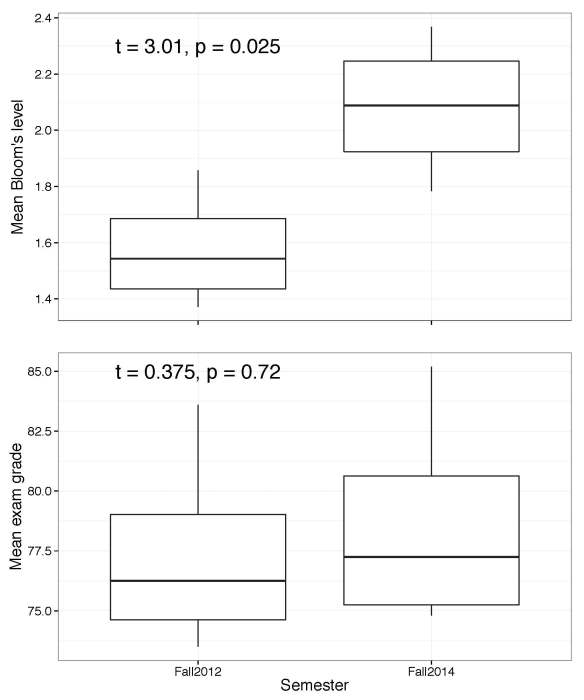

After going through each of the four exams from both years, I calculated the mean Bloom’s level for each exam and then used the four exams as replicates within a year.* Ideally we’d have more years to compare, but there were too many other factors that changed with other semesters.

What did we find? We found that the exams asked students to think at higher levels, but there was no difference in performance on the exams in the two years (if anything, they did a little better on the harder exams):

In other words, we asked more of our Intro Bio students and they rose to the challenge. To me, this is really exciting evidence that all the effort we put into overhauling the class was worthwhile. But you could argue we still have a way to go — is an average Bloom’s level of 2 high enough for Intro Bio? I truly don’t know, and this is something I should think about more.

It does raise an interesting question: if students are learning more, should grades go up? Does every student deserve an A? The answer to the second question is clearly “no”. (Edited to add: I say “no” because, while the overall performance went up, some students still clearly did not grasp the material, let alone master it. If everyone had mastered the material, I’d happily give everyone an A.) The answer to the first question is less clear. The new model we’re using for the class requires the average student to spend much more time on the class, which surely contributes to the increased performance. Should that be rewarded? I feel okay with the grade distribution being slightly higher (say, a tenth of a point) than it traditionally has been, because I think we can demonstrate that our students are learning more. But I don’t think there should be a substantial shift. There’s still a wide range in performances on the exams – with 650 students, we naturally get a normal distribution on exams. I think the grades should reflect that variation.

I also think it’s worth pointing out that the previous exams weren’t easy. They were difficult in their own way. I’m not sure how well I would have done on them as a student, to be honest, because they required memorizing lots of facts and I’m not particularly good at memorizing. I think they were hard because students had to jam a lot of information in their brains and then spit it back out. I suspect most of them forgot that information before long. My hope is that, by having repeated testing on the same topics (via the quizzes) and then by needing to work with the information at a higher level (including on the exams), the information and skills the students learned in the new format of the course will stick with them for much longer.

What I would love is to follow up with these students in a few years to see how they’re doing. Are they retaining more information from Intro Bio when they arrive in upper-level ecology, evolution, and genetics? Do they come in with better process of science skills (e.g., figure-reading abilities)? I would love to know! The problem is that we don’t have a good control group, since we’ve fully shifted to the new format. Given that, I’m not sure how to tackle these questions. But I hope we come up with a way, because I would love to know if this format has longer term benefits for our students, too.

*Data and code are available on GitHub.

Update 6/12/15: People have been asking for the answers. I should have thought to include them! Here’s a key:

Level 1 question: A

Level 2 question: B

Level 3 question: C

Level 4 question: C

I don’t understand why you are so committed to giving a lot of students low grades when they have learned more than in previous years. I feel like the grading curve really disadvantages students who did not go to the fancy high schools, and these are just the students we pretend to want to retain in STEM. Why not make it possible for everyone, everyone in the class to get an A if they learn the material to a certain level? Why not have additional chances to show they have done that so those that are less experienced with effective learning have the chance to make it to the highest level? After all, if we have a physician that takes longer to learn something, we work with her until she gets it. All the standard way of grading does is perpetuate stereotypes, hurt people who did not learn earlier how to study and so on. If a student learns the material on the first, second, or third try, give them the good grade and show them they can do it! I think along with the revolution in teaching we need a revolution in grading and we need to stop talking about grade inflation. We need to pay attention to what real learning is.

I’m certainly not committed to giving a lot of students low grades. The reality is that, while the overall performance went up, some students still clearly did not grasp the material, let alone master it, which is why I said that not everyone should get an A. If everyone mastered the material, I’d happily give everyone an A.

Congrats on a great semester!

It is an interesting issue (and I mean this genuinely, not as a euphemism) about what relationship we should have between teaching effectiveness, expectations, and grade distributions. People who have low expectations that all of the students meet presumably have a high average grade. But people with high expectations, and when students meet them, might have equivalent grades, but will have learned more. What does a grade mean? A major component of the grade isn’t about learning, but just how well the student met the expectations of the professor. So grades only mean what we want them to, by articulating them to our expectations.

I’m sorry, but people who want everyone to get a gold star, completely miss the point of the educational system and the grades it assigns.

“A” does not mean “learned the material to some level”, it means “several standard deviations above average”.

There is nothing wrong with being average (“C”), and at the same time, there is a _lot_ wrong with giving someone who is _not_ several standard deviations above average, an “A”.

The problem that (i.e.)@JoanStrassmann ought to be trying to fix, is the stigmatization of being average, not the a grading system that helps us identify a students strengths and weaknesses.

I disagree. I think if you show mastery of the material above a specific level then the student deserves an A. Grades are not meant, in my view, to compare one student vs the other, but to assess how well they learned and can use the material presented in the course. This has nothing to do with giving everyone a gold star.

It IS possible for EVERYONE to do very well. If everyone has learned the material taught, why do you assume they have a weakness in the subject matter?

I once was a part of a high school sculpture class that was doing 2nd year college level work. A state inspector came to this teacher’s classroom, and the write up basically said, “This guy isn’t following the state curriculum, but we should let him alone.” That was back when teachers still had some freedom in the classroom.

I agree with your point of view. Personally, I’d prefer knowing how I stacked up against the mob, instead of living in a fish bowl. Certainly GRE scores communicate where you stand in the pack, so why not do this at all stages of education?

When I took 2 semesters of organic chem back in the 80s, my exam scores were the highest the institution had ever seen. As far as I know, the record stands. Obviously, I earned an “A” both semesters, but the grades were curved per semester. As such, nothing distinguishes my “A” from any other.

I would think employers would love a system where grade inflation was sent to the landfill, and no matter your alma mater, they would know how you stack up.

Hey Meg- Great topic! I think students would much rather be challenged instead of coddled- and that they respond to challenge- even if at the time they resent you for it. So kudos for making the course more of a challenge.

Concerning the “uptick” of grades- and how to control for that- I had an experience as an undergraduate when I took a course in psychological statistics. The professor was hard core stats form start to finish. The exams were grueling, and as far as I know, no one ever finished one of them. I would always leave an exam feeling dejected and pretty much worthless.

The prof graded his students (at the time I took the course) on 27 years worth of exam scores. It was as bell-shaped a curve as you could imagine. Even though I never finished one of his exams, I ended up with a “B” for a final grade. Turns out that was a good reward, because it was extremely difficult to get more than one standard deviation from the mean when 27 years of scores were used for grading.

So one way to control for the fluctuations you mention would be to apply many years of scores to your curve, and then no one particular strange outcome will cause the pattern to shift.

Interesting technique because it implies that the instructor was just as good 27 years ago as they are today…

Interesting – I intend to do a similar audit of our exam questions this summer as think we could be pushing ours a lot harder, so interested to see your experiences

The sad thing that I have noticed about my exams over three semesters is that when we give them 5 choices to MC questions instead of 4, the median drops 10-15%.

Pingback: First ever Georgia Tech School of Biology teaching retreat | Jung's Biology Blog

Pingback: Having an Organism of the Day was only sort of successful | Dynamic Ecology

Pingback: What are the key ecology concepts all Intro Bio students should learn? | Dynamic Ecology

Pingback: Poll: What’s your preferred number of times to teach a particular course? | Dynamic Ecology

Pingback: What if we make a class better for student learning but unsustainable for faculty? | Dynamic Ecology

Pingback: Why teaching Intro Bio makes me think we need to radically change qualifying exams | Dynamic Ecology

Really minor point, but the answer to question 4 seems like overreaching without more context. I’d say the patterns are consistent with C, but they’re consistent with other consumer-resource and competitive (indirect ecosystem-engineering) scenarios too. Do we call all those cases parasitism? I thought parasitism involved direct (partial) consumption of the other organism. Heck, this is my subfield… I should study up!